courtesy: PromoTurismoFVG

By Stephen Brewer

Hit the Heights . . . and see the sights, smell the coffee, savor the food and wine, and soak in the sun on golden beaches. They’re all part of discovering the Friuli Venezia Giulia region, tucked away in Italy’s northeastern corner.

courtesy: PromoTurismoFVG

From top to bottom—from the craggy pinnacles of the Dolomite mountains to languid lagoons along the Adriatic coast—Friuli Venezia Giulia delivers alpine scenery, beaches, Roman ruins, amazing food and wine, Hapsburg palaces . . . well, just keep scrolling to experience the many pleasures tucked away here in Italy’s northeastern corner.

courtesy: PromoTurismoFVG

Getting a high in Friuli Venezia Giulia often means climbing one of the Dolomites, the range of spectacular pinnacles that sweep across Italy’s northern frontier. No need to put on mountaineering gear to scale a formation as imposing as the Campanile di Val Montanala—you can also appreciate the pristine alpine wilderness from hundreds of miles of trails that crisscross the region’s two vast nature parks.

courtesy: PromoTurismoFVG

Aquileia

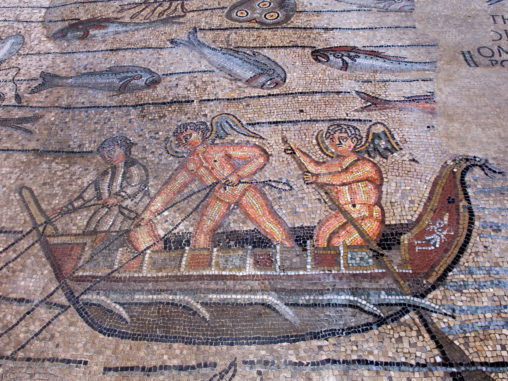

You may not have heard of tiny Aquileia, on grassy coastal plains a few miles inland from the Adriatic, but in its heyday the once-bustling port was one of the largest and wealthiest towns in the Roman Empire. Intriguingly, most of the ancient city still lies under the surrounding fields, waiting to be unearthed.

courtesy: PromoTurismoFVG

Attila the Hun laid waste to Aquileia in the fifth century and residents fled south and founded Venice. But it wasn’t long before Aquileia rose again. This time, the city became one of the most important centers of early Christianity. In the Basilica, one of the largest stretches of floor mosaics in the Western world colorfully depicts biblical scenes and other religious motifs.

courtesy: PromoTurismoFVG

Grado

Not too much has changed since the days when Grado was a fashionable beach resort for the mostly landlocked Austro-Hungarian Empire. For that matter, even Roman legionnaires came to the so-called “Golden Island” to kick off their sandals and soak their dusty feet. Behind two miles of soft, sun-soaked sands are fisherman’s houses, quay-lined canals, and ancient churches facing stony squares.

courtesy: PromoTurismoFVG

Narrow alley-like streets wind their way to the lungomare, a seaside walkway where just about everyone in town turns out for the evening passeggiata.

courtesy: PromoTurismoFVG

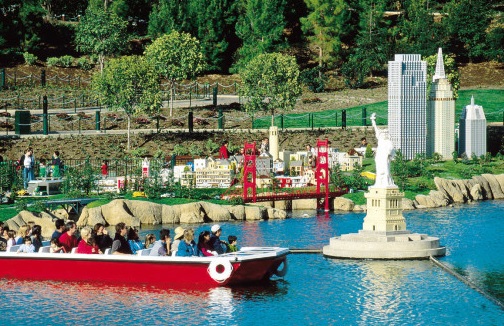

The Grado Lagoon

A string of shallow lagoons stretches south from Grado all the way to Venice. Time was, fisherman would row and sail across the shallow tidal waters on flat-bottomed boats called bateli, and spend days at a time on hundreds of little islands in casoni, primitive, straw-roofed huts.

These days you can glide through the lagoon on pleasure boats, or for a bit of exercise, canoe or kayak (check out the guided trips here). However you propel yourself, you’ll spot herons and other waterfowl and watch grasses and sandbars emerge then disappear again in the shifting tides. Somewhere along the way, it’s almost mandatory to dock at Ai Fiuri de Tapo or another simple waterside restaurant, where fresh fish practically leap from the water onto your plate.

courtesy: PromoTurismoFVG

Friulian Wine

Some of Italy’s finest whites come from the gentle hills of the Collio, where a gentle, sunny microclimate ensures the terraced hillsides explode with cascading vines. A tasting at esteemed winery Russiz Superiore —or better yet, a feast in the estate’s vast cellar—shows off the crisp refinement of several Riserva whites, but for that matter, a sip of one of the reds will probably have you stashing a bottle or two in your luggage, too.

courtesy: PromoTurismoFVG

Food

And speaking of food and wine: the region’s Prosciutto di San Daniele, as any resident will tell you, is far superior to the harsher, less sublime, one might even say more vulgar Prosciutto di Parma. Then there’s montasio, a creamy mountain cheese, and white asparagus from Tavagnacco. These and other regional specialties get star treatment at La Taverna, outside the pretty little walled village of Colloredo di Monte Albano.

courtesy: PromoTurismoFVG

There, acclaimed chef Ivan Bombieri turns even a classic pasta with tomato sauce into a memorable masterpiece. Mr. Bombieri’s creations are as warm and unpretentious as he is, and in good weather they’re served in a garden that’s a little slice of heaven that does justice to the dishes placed in front of you.

courtesy: PromoTurismoFVG

Trieste

A strong wind, known as the bora, often blows over Trieste, the region’s elegant seaside capital, hugging the border with Slovenia. With the gales have come everyone from Jason and the Argonauts, Byzantine sailors, and most notably traders who made vast fortunes when the elegant city was the principal port of the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

courtesy: PromoTurismoFVG

The House of Hapsburg left behind the airy Piazza Unita della Italia, their seat of commerce, and Castello di Miramare, the seaside palace built for Austrian Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian and his wife, Charlotte, between 1856 and 1860.

courtesy: PromoTurismoFVG

These regal assemblages, along with broad boulevards, airy seaside promenades, squares lined with sidewalk cafes, the hilltop cathedral of San Giusto, a Roman theater, even the city’s own Grand Canal are all tinged with salty exoticism and a heady dose of international flair.

courtesy: PromoTurismoFVG

Also wafting on the city’s famous breezes is the strong scent of coffee. Trieste might be Italian these days, but the city’s legendary coffeehouses are Viennese holdovers. Belle époque Caffe delle Specchi, early 20th-century San Marco, pastry-scented Bomboniera—every Triestene has a favorite spot to linger. Where there’s strong coffee and cozy ambiance, there’s usually a writer or two in residence. Irish novelist and poet James Joyce lived in Trieste for 14 years and wrote his best-known works here, including Dubliners, Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man, and parts of Ulysses.

courtesy: PromoTurismoFVG

Udine

Legend has it that Attila the Hun commanded his troops to use their helmets as shovels to create the hill that’s now topped with Udine’s castle.

Another industrious passer through was the artist Tiepolo, who came from Venice in 1726 to paint frescoes in the Patriarchal Palace. His wonderfully colorful and expressive depictions of the Sacrifice of Isaac and other Old Testament scenes are bathed in light and are engagingly dramatic.

Monumental undertakings aside, these days Udine seems relaxed and easygoing, a place to stroll down medieval lanes and stop for a glass of wine or coffee in Piazza Matteotti.